Dharma Talk given by Thich Nhat Hanh on August 13, 1997 in Plum Village, France.

© Thich Nhat Hanh

Good morning, my dear friends. Today is the thirteenth of August, 1997, and we are in the Upper Hamlet. We still have one paramita to learn.

Good morning, my dear friends. Today is the thirteenth of August, 1997, and we are in the Upper Hamlet. We still have one paramita to learn.

Paramita means perfection, the perfection of the crossing over to the other shore. We have seen that a paramita is not so difficult to practice; even children can do it. Paramita means from this shore of suffering we cross over to the other shore, the shore of well-being. From the shore of anger, we cross to the shore of non-anger. From the shore of jealousy, we cross over to the shore of non-jealousy. If you know how to do it, you can cross over to the other shore very quickly. It is a matter of training, it is a matter of practice, and you can do that with the help of another person or many other persons. It’s nice to cross the stream of suffering together, hand in hand. So every time you want to cross, if you feel that alone it would be a little bit too difficult, you ask someone to hold your hand and you cross together the stream of suffering with him or with her.

If you feel you are caught in anger and that anger is a kind of fire burning you, you don’t want that; you don’t want to stay on this shore suffering from anger—you want to get relief, you want to cross to the other shore. You have to do something. Row your boat to go to the other side. Whether that is walking meditation, mindful breathing, or anything that you have learned here from Plum Village, it can be a boat helping you to cross over to the other shore. Next time when you feel that you don’t like it on this shore, you have to make a determination to cross to the other shore. You may like to say to a person that you love that you don’t want to stay here on this shore, you want to cross over to the other shore, and you may like to ask the other person to help you to cross. There are many things we can do together. Sitting and listening to the bell—we can do together, as two brothers, two sisters, as mother and child, or father and child. We can sit down and practice together.

I know a young mother who has a little boy of four years old, and every time the boy is agitated, not calm, not happy, she will take his hand and ask him to sit down and practice breathing in and out with her. She told her child to think of the abdomen, the belly, and breathing in seeing the belly expanding, rising, and breathing out seeing the belly falling. They practice breathing together like that three or four or five times, and they always feel better. If the mother left her baby alone to breathe, it would be a little bit difficult for him because he is so young, he cannot do it alone. That is why the mother sits next to him, and holds his hand, and promises to practice breathing in and out together. I have seen that, I have seen the mother and the child practicing in front of me. Because one day I had tea with them—the little boy wanted to have tea with me—so I offered him some tea, and we had a nice time together. Suddenly there was something, he became unhappy and agitated, so his mother asked him to practice that in front of me, and both did very well. So mother has to learn to practice with her child. Father also has to learn to practice with his child. This is a very good habit, a very good tradition, a husband has to learn to do it his wife, a partner has to learn to do it with her partner.

Every time there is one of us who is not happy, we have to help him, to help her, to go to the other shore. We have to support him, support her. We shall not say, “That is your problem,” no. There is no such thing as your problem; it is a problem for everyone. If one person suffers, then everyone around has to suffer too. If a father tells his son or his daughter, “That is your problem,” that means the father has not got the insight. There is no such thing as your problem, because you are my son, you are my daughter, and if you have a problem, that is our problem, not yours only. Because if happiness if not an individual matter, suffering also is not an individual matter. You have to help and support each other to cross the river of suffering. So next time when you feel unhappy, you cry, you don’t want to be unhappy, then you may like to ask your father, your mother, your brothers, and your sisters to help. “Please help. I don’t want to stay on this shore. I want to cross over.” Then they come and they will help you. He, she will help you.

You should know the practice. We should know how to practice walking meditation, to practice sitting and breathing in and out with our attention focused on our belly. We can invite the bell, to listen together. Every time you feel unhappy or angry, always you can practice listening to the bell. I guarantee that after having practiced three sounds of the bell, you will feel much better.

That is why it would be very helpful for each family to have a bell, a small bell, at least. I don’t know whether they have small bells available in the shops, but I think that a bell is very useful. That is why children who come to Plum Village, they are always taught how to invite a bell. If we use a bell, then the whole family has to practice together. It’s not possible that one person practices the bell and all the others talk and don’t practice. We have to make an agreement within the family that every time there is a sound of the bell, everyone will have to stop—not only stop talking but stop thinking—and begin to breathe in and breathe out mindfully. Your breathing will become deeper, slower, and more harmonious after several seconds. You know you are crossing while you breathe in and out mindfully and listen to the bell. You are actually crossing the stream of suffering. Maybe in Chinatown you can find a bell somewhere, and I think that Plum Village has to arrange so that there are bells in the shop, so that everyone in the family can get one.

I propose that in each home, each family, there be a bell, and I propose that we arrange so that in each house there is one place to practice listening to the bell and breathing in and breathing out. In our house, there are rooms for everything. There is a room for guests, there is a room for playing, there is a room for eating, there is a room for sitting, for everything. Now, as a civilized family, we have to invent another room. I call it the breathing room. Or you might like to call it the practice room, or meditation room—a room that is for the restoration of peace, of joy, of stability. It is very important. You have a very beautiful room for television, and you don’t have a room for your own peace, your own joy, your own stability. That’s a pity. No matter how poor we are, we have to arrange so that we have a small place, a room in our family, to take refuge in every time we suffer. That room represents the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. When you step into that room, you are protected by mindfulness, by the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. Children have to take care of that room. Because according to the practice, once they get into that room, no one can shout at them any more, including parents, because that is the territory of peace. You can take refuge in that, and no one can shout at you and chase after you any more. It is like the compound of an embassy. The compound of an embassy belongs to the territory of that country, and no one can invade that.

That is why in each home we should have such a room, very sacred. You should not use that room for other purposes. You should not go into that room to play chess, to play the radio, to do other things. That room is just for the practice of breathing, of listening to the bell, of sitting meditation, of listening to the dharma talks, dharma discussions. That room should be only for peace, for the restoration of peace and joy. When you know that there is someone in the room practicing, you should respect that, and not make a lot of noise. You know when you drive through a zone where there is a hospital, you know that many sick people are in the hospital and they need quiet—that is why you don’t blow the horn, you don’t make a lot of noise. The same thing is true when you know that there is someone in a meditation hall, in the breathing room; you should try not to make noise in the house. If mother is in the meditation room, then you should turn off your phonograph or your television. This is a very good practice.

Every time you get angry, you get upset, you suffer, you know that you need the breathing room. So you think of the breathing room, and as soon as you begin to think of the breathing room, you feel already a little bit better; you know what to do. You don’t accept to stay there without doing anything, just to be a victim of your anger, of your suffering. That is why you slowly stand up, you breathe in, breathe out mindfully, and you begin to walk in the direction of the breathing room. “Breathing in, I make one step, breathing out, I make one step.” When people see you doing like that, they will have a lot of respect: “This person, although she is very young, she knows how to take care of her anger and her suffering.” Everyone will be looking at you with respect, and they will stop laughing and talking loudly; they might follow their breathing to support you. That is the practice. Mother and father—who have received the teaching, who know what it is like to be in anger, who know how to practice when they get angry—mother and father will stop talking and breathe in and breathe out and follow you with their eyes, until you open the door and enter inside. Holding the knob of the door, you breathe in; pulling the door, you breathe out; and you go into it and you close the door behind you peacefully. You bow to the flower in the room—because it would be wonderful to keep one flower alive in that meditation hall, any kind of flower. That flower represents something fresh, beautiful, the Buddha inside of us.

You don’t need a lot of things in that breathing room. You need only a pot of flowers—if you have a nice drawing of the Buddha, you can put that—otherwise, one pot of flowers, that will be enough. And one bell, one small bell. I trust that when you go home you will try your best to set up that important room within your home. And you bow to the flower, you just sit down. Maybe you have a cushion—a child should have his or her own cushion—and you need a cushion that fits you, where you can sit beautifully and with stability for five or ten minutes. Then you practice holding the bell in the palm of your hand, you practice breathing in, breathing out, as you have been instructed, and then you invite the bell, and you practice breathing in and breathing out. You practice listening to the bell and breathing in and out several times until your anger and your suffering are calmed down. If you enjoy it, you may like to stay there longer.

You are doing something very important—you are making the living Dharma present in your home. Because the living Dharma is not a Dharma talk. A Dharma talk may not be a living Dharma, but what you are doing—walking peacefully, breathing mindfully, crossing the river of anger—that is a real Dharma and you, it is you who are practicing, who are crossing, so you inspire a lot of respect. Even your parents have to respect you because you embody the Dharma, the living Dharma. And I will be very proud of you. If I see you, I will know that you are doing so.

I know of a family in Switzerland, a family of seven or eight brothers and sisters, a very big family, and they spent time in Plum Village, they learned about these things, and one day while they were home they got into a kind of dispute. Usually one month or two after coming back from Plum Village, you can still keep the atmosphere of peace alive. But beyond three months, you begin to lose your practice. You become less and less mindful, and you begin to quarrel with each other. So that day, everyone in the family was talking at the same time—all the brothers and sisters except one, the youngest. She suffered, she didn’t know why all the brothers and sisters quarreled and suffered at the same time, so it was she who remembered that the bell is needed. So she stood up and reached for the bell, she breathed in and breathed out, and she invited the bell, and suddenly mindfulness came back. Everyone stopped shouting at once, everyone was breathing in and out, and after that everyone burst out laughing, and laughing, and laughing, and made peace with each other. That was thanks to the youngest member of the family. I think she was five at that time. Now she is fourteen, and she is here now today.

[Bell]

If you are an adult, you can practice like that, like your child. Every time you get angry at your husband, at your wife, at your brother, or at your child, you can do like that. Instead of arguing and shouting, you stand up, you breathe in and out, and you practice walking meditation to your breathing room. Your child will see it, your husband, your wife, will see it. They will have respect for you, they know that you are able to handle your anger, to take care of yourself, to love yourself. They will stop what they have been doing, and they may begin to practice.

When you are in the breathing room, inviting the bell, listening to the bell deeply, and practicing breathing, one of your children may like to join you. So while breathing, you may hear the sound of the door opening smoothly. You know that someone in the family is joining you; that may be your child, that may be your husband or your wife. You feel much better that you are not practicing as an individual any longer, but you are practicing as a sangha. That will warm up your heart, as you feel that someone is sitting close to you and beginning to breathe in and breathe out—this is wonderful. Maybe the person—the person who made you angry—after a few moments, feels that he will have to join you in practice. Then you hear the door opening again, and there, he’s coming and sitting close to you, and you are flanked by the two people you love the most in the world, practicing breathing in and out. There is no one to take a picture of all of you, but that is the most beautiful picture that could be taken of the family. Maybe you do not have any lipstick or powder on your face, you do not wear the best dress, but there you are in the most beautiful state of being, because all of you know how to practice. All of you embody the living Dharma at this moment. This is something we have to learn—this is a good habit, it’s a good tradition, and you are truly the sons and the daughters of the Buddha.

I would like to transmit to the young people today something that they may use in the future. That is a cake. But this cake is not visible now. If it happens that your mother and your father get into a dispute—that happens from time to time—and you don’t like these moments, the tension in the family, the disagreements between your father and your mother. The tension is coming up, one of them said something not very nice to the other, and you suffer. It is like the sky just before a storm. It is a heavy, oppressive atmosphere and a child always suffers in such a condition. I have been a child, and I did suffer when the atmosphere in the family was heavy and oppressive like that. But you know that you should not continue to be a victim because it’s not healthy to stay long in such an atmosphere. You should do something. There are children who try to run away, but their apartment is too small and they are on the fifth floor. There is no garden around. So they could not get away.

Many children choose to go into the bathroom and lock the door to avoid the tension and heavy atmosphere in the family. Unfortunately, even in the bathroom the atmosphere was still felt. It’s not healthy to be in such an atmosphere. Father and mother do not want to make their child suffer, but they cannot help it—they get into a tension, a conflict. In that moment, I would suggest that you do this: you pull the dress of your mother and you say, “Mommy, it seems that there is a cake in the refrigerator.” Just do that; this is another mantra that I am transmitting to you. Whether there is a cake or there is no cake in the refrigerator, you just open your mouth, after having breathed in and out three times, and you say, “Mommy, there is a cake in the refrigerator.” Just say that.

It may happen that there is a cake. Your mother will say, “That’s true. Why don’t you bring some chairs to the backyard? I will make some coffee and bring the cake down for you and for your daddy.” She will say that, and she will take the excuse to withdraw to the kitchen. Because she also wants to cross to the other shore; she doesn’t want to stay there forever and get destroyed. But if there is no pretext, it would be impolite, provocative, to just leave like that. So you help her. You say, “Mommy, it seems that there is a cake in the refrigerator,” and she will know, she is intelligent, she knows what you mean. You mean that you don’t want this to continue. Then when you hear your mother say this, you say “Yes!”and you run, you run away. You run to the backyard, you arrange some chairs and you clean the table back there. Your Mommy will go into the kitchen, she will boil some water for tea, she will ask you to come and help bring the cake to the backyard and so on. Both of you are doing these things and practicing mindful breathing together. It is very nice, and I will be very proud of you both. You know that you can do it. Please.

Then your father, left alone in the living room, he has seen that, and he has been in Plum Village, so he knows that his wife and his child are practicing. He feels ashamed if he doesn’t practice. So he stays there and practices breathing in and out also. He may join you in the backyard with the cake, and the three of you will be over to the other shore in just ten minutes. Don’t worry if there is no cake in the refrigerator because your mommy is very talented. She can always fix something.

So this is a cake that I want to transmit to you today, a cake that never disappears. This kind of cake is forever. This is one way of practicing paramita—crossing over. There are many Dharma doors. Dharma doors mean methods of practice. The breathing room is one Dharma door, a wonderful Dharma door. In the next century that’s coming in two years, I want to see in every home a breathing room, a sign of civilization. If you are a writer, if you are an artist, if you are a reporter, if you are a novelist, if you are a film maker, please help. If you are an educator, a Dharma teacher, please help. In every home, there will be a breathing room for us to take care of our nerves, of our peace, of our joy. We cannot be without a breathing room. So the breathing room is one Dharma door that we have to open to the new century, and the cake is also a Dharma door.

When you hear the bell, please stand up and bow to the sangha before you go out.

[Bell]

The last pebble, we call it virya paramita: the continued growth, the continued transformation. We know that when we cook potatoes, we have to keep the pot covered and should not take the lid off because the heat might get out. Also, we have to keep the fire on underneath. If we turn the fire off, then the potatoes could not cook. After five minutes, if we turn the fire out, then we cannot expect the potatoes to cook, even if we turn on the fire for another five minutes, and we turn it off. That is why there should be continued progress, continued practice, the continuation, the steady practice—that is called virya.

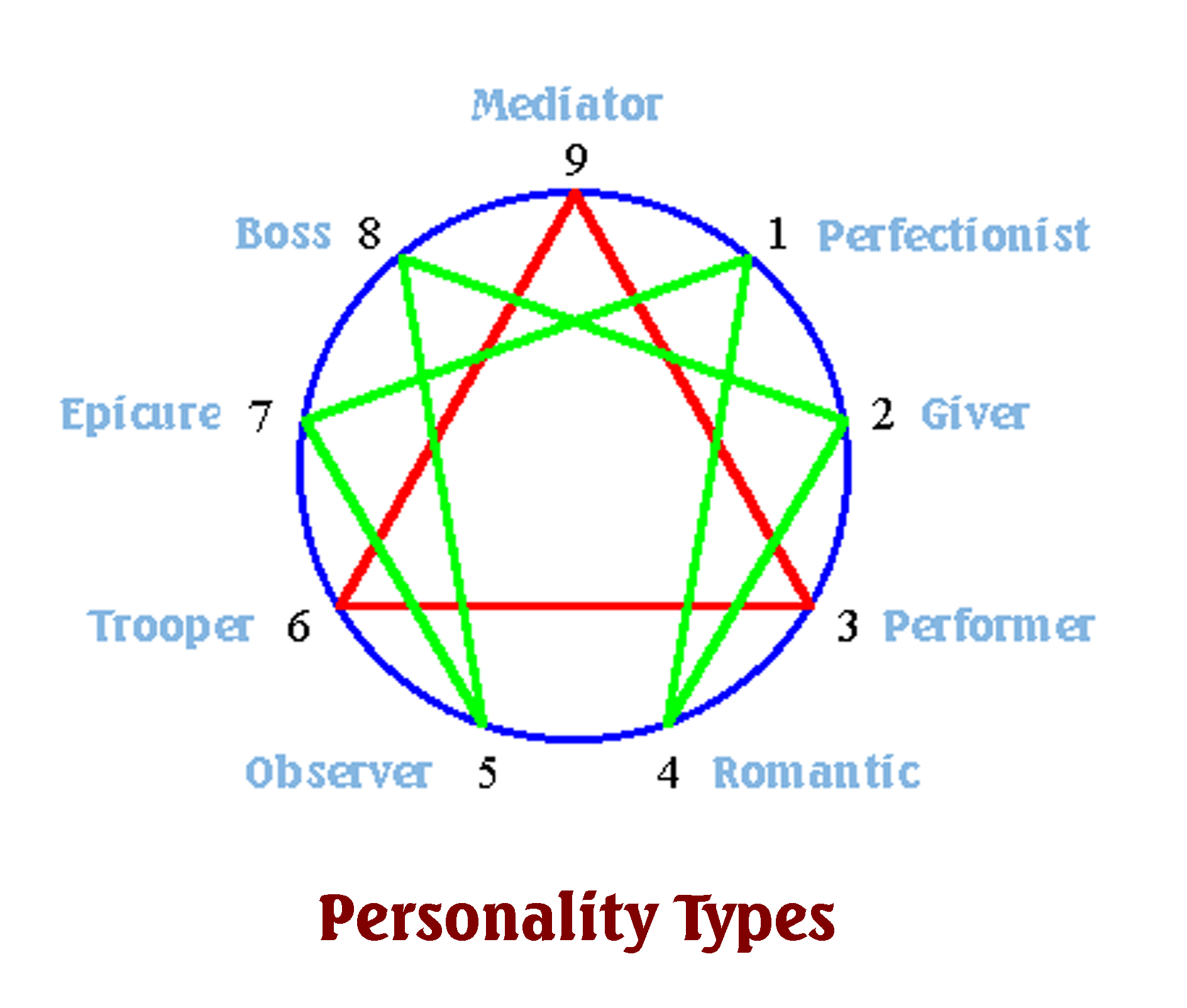

In terms of consciousness, we know that there are seeds to be watered and there are seeds to be transformed, and if we can continue to water the positive seeds and to refrain from watering the negative seeds, instead we know how to transform them—that is the process of continued transformation. Let us visualize our consciousness. This circle represents our consciousness, and the lower part is called “store consciousness” (alayavijñana) and the upper part is called “mind consciousness”(manovijñana). [Thay draws a diagram.] We know that in our store consciousness there are all kinds of seeds, positive and negative, buried here, and there are something like 51 categories of seeds. If it is a negative seed, the practice consists in preventing it from manifesting itself in the upper part of consciousness. You recognize that there is a negative seed in you and you would not like it to be watered, because if it is watered then it will have a chance to manifest itself in the upper level of your consciousness and it will become a mental formation.

Suppose this is a seed of anger. As far as it accepts to stay still in the store consciousness, you can survive, you are fine, you can smile, you can be joyful, you can even be happy with the seed of anger in you, with the condition that it accepts to stay still. But if someone comes and waters it, touches it, or you yourself water it, then it will manifest itself on the level of mind consciousness. And there is a zone of energy called anger, and it makes the whole scenery unpleasant. It may stay here for some time, maybe for a few minutes, sometimes a half hour, sometimes the whole day, and the more it stays, the more you suffer. And the more it is here, manifested, the stronger it becomes at the base. So if you allow it to manifest, you get two disadvantages. The first is that you suffer up here, and the second is that it grows bigger here. That is why the practice of virya consists in not giving it a chance to manifest.

So if you love yourself, if you care for yourself, you have to arrange so that you will be protected, you will not touch it and water it, and you ask your friends not to water it. “My dear, if you really love me, don’t water that negative seed in me. You know I have that weakness, I have that seed in me. If you water that seed in me, I will suffer and you will suffer too.” So if we love each other, we should know each other, we should know the negative seeds in each other, and we should practice so that we do not water them every day. This is the practice of virya. We should plead with the people around us. “Dear people, you know me, you know my weakness, you know these seeds in me. So, please, if you love me, if you do care for me, please refrain, please do your best to protect me and not to touch, to water these seeds in me.” We have to sign a peace treaty. We don’t practice alone, we practice with a sangha, with the people we love, also.

If it has already manifested, then we should know the ways to embrace it and to help it go back as soon as possible to the store consciousness. Because the sooner it goes back, the better you can feel; because here you don’t have to suffer long, and down here it doesn’t have a chance to grow too big. That is the first meaning of virya. The negative should not be encouraged to manifest. And if it has manifested, do whatever you can to take care of it and to have it go back down here as soon as possible.

Third, the good seeds. Please do whatever you can in order for them to manifest as wholesome mental formations. If you know how to love yourself, to take care of yourself, then please look and realize that you have good seeds in you, seeds that have been transmitted by your ancestors, your teachers, your friends. You do whatever you can to allow them a chance to manifest. Because mind consciousness is like a living room, and you would like to invite into your living room only the pleasant people. With a beautiful pleasant person in your living room, you know it is very pleasant, you enjoy it. So don’t allow your living room to be visited by unpleasant people. Invite only beautiful people, pleasant people to be there. That is the third practice of virya. You do that by yourself. You have all the seeds of happiness in here. You have a poem, you have a song, you have a thought, you have a practice, and every time you touch that, you invite it to the upper level of your consciousness and then you feel wonderful, and you keep it in your mind consciousness as long as possible.

Your mind is like a television set, or rather, it is like a computer with many hard disks down here. This is the screen of your computer, you can invite whatever you have down here up there. Selective invitation, that is your practice. You invite only the things that are pleasant. Sometimes the pleasant things are buried down here under many layers of unpleasant things, so you need to help, so that you can take these jewels up to the screen. Leave them up as long as you can, keep them as long as you can, in the upper level of your consciousness. A piece of music, a poem, a happy souvenir, the seed of love, the seed of compassion, the seed of joy—all these positive seeds in you should be recognized and should be touched, should be invited. You ask the people around you, the ones who share your life, “Please my darling, please my friends, if you really love me, really want to help me, please recognize the positive seeds in me and please help these seeds to be touched, to be watered every day.” That is the practice of love. To love means to practice selective watering of the seeds within the other person and within yourself.

Whatever good, pleasant seed is manifested here, we try our best to keep it as long as we can. Why? Because if it stays long in here, at the base it will grow. This is the teaching in the abhidharma, the Buddhist psychology. Buddhist psychology speaks of consciousness in terms of seeds. Bija is a seed and we have all kinds of seeds within our store consciousness. Store consciousness is sometimes called the totality of the seeds (savabijaka). Seeds transform into mental formations. Unwholesome seeds are born here in the mind consciousness as unwholesome mental formations. Wholesome seeds are manifested as wholesome mental formations.

So take care of your living room. Take good care of the screen of your computer and do not allow the negative things to come up. And allow, invite, the positive things to come up and keep them as long as you can. There will be a transformation at the base if you know how to do it. This is the virya paramita: continued practice, continued growth, continued transformation—it should be the same.

[Bell]

Now we should go back to other paramitas. [Thay writes on board.] First is dana (giving). Second is prajña (insight). This is shila (precepts or mindfulness training). This is dhyana (meditation), consisting of stopping and looking deeply. And this is ksanti, translated in Plum Village as inclusiveness. If you only participated in one of the four weeks in Plum Village, you may like to listen to other dharma talks in order to understand, to have a clearer and deeper understanding of the other five paramitas. We have been showing the nature of interbeing between the six paramitas. If you practice one of the paramitas deeply, you practice all six. You cannot understand one paramita unless you understand all the other five.

So continued practice here means that you continue to practice giving; you continue to practice the mindfulness trainings, you continue to practice inclusiveness (embracing whatever there is), continue to practice stopping, calming, and looking deeply. And you continue to practice understanding. All five are the contents of the sixth. And this is true of all of the paramitas. We have used dana paramita as an example, because understanding is a gift, a great gift. To be able to stop, to calm, and to look deeply is a great gift. To continue your practice is a great gift. To practice embracing everything, including what you may think to be unpleasant in the beginning, that is also a gift. Living according to the five mindfulness trainings is also a great gift. So you cannot practice giving unless you practice the five other paramitas. And this can be applied with all the paramitas, the interbeing of the six paramitas.

In the beginning, I told the children that you don’t need money at all to practice dana. You offer your freshness, you offer your presence, you offer your stability, your solidity, your freedom. That’s a lot already. And these things can be cultivated by the practice of the other paramitas.

All the six paramitas have the power to carry us over to the other shore so that we will not suffer anymore. After some time, training yourself, you’ll arrive at the state of being when you can cross the stream of suffering very easily and very quickly. You have to master the practice, and you are no longer afraid. It is like knowing how to make tofu. If you know that there is no longer any tofu in the house, you are not afraid. A few hours and then you have tofu again. You know how to garden, to practice organic gardening. You know that there are heaps of garbage in your garden. You are not afraid because you know how to transform the garbage back into compost, and you are not afraid at all. While transforming the garbage into the compost, you can be very joyful. Therefore, we are no longer afraid of the garbage in us, the afflictions, the suffering in us. We know how to handle them, how to transform them; therefore, crossing to the other shore is a joy. You don’t have to suffer even while crossing. You don’t think that only when you arrive at the other shore you stop suffering, no. Crossing is already a pleasure.

It’s like a child, when she knows that there is a breathing room, she stands up, and she practices walking meditation to the breathing room, and she already feels better because she knows the way, she knows what to do. So if you train yourself in the six paramitas, they will become a habit, a tradition, a routine; and every time you want to cross, you just cross, and not making a lot of effort, you just cross. It’s like how you walk, you practice walking meditation. And you will not suffer any setbacks. You train yourself until you arrive at the state of being called the state of no setbacks, always progressing, not backsliding. That is the meaning of virya. You have mastered the techniques, the ways. That is why you never go back to the state of utmost suffering in which you were caught before.

Life is a continuation of transformation; it’s just like gardening. You cannot expect that your garden will only produce flowers—your garden does produce garbage. That is the meaning of life. Those who suffer don’t know the art of transformation—that is why they suffer, because of the garbage in them—they don’t know how to transform. But you, you know the art of transformation; that is why you can embrace even your suffering, and you are able to transform. You never get back to the state of being overwhelmed, not knowing what to do with your suffering. If you train yourself in the six paramitas, one day you will feel that you are no longer afraid of any suffering. It’s like doing the dishes. Of course, every day you have to use dishes, you have to eat, and therefore you produce dirty dishes. But for us, making dishes clean is very easy. We have detergent, we have water, we have soap, we have the time, we know how to breathe in, breathe out, how to sing while doing the dishes. So doing the dishes is no longer a problem. It can be very joyful. So you don’t suffer a setback any more, just because you know the way, you know the paramitas, you have the boats to cross over to the shore.

In the bell there are a few questions that I have not answered. The newest questions that I have are these two. “Thay, why don’t I feel that I love myself? I am unable to love myself.” That is one question. And the other question is: “Without anger, without hate, how could I have the energy to work for social justice? How could you really love your enemy? If you love your enemy, what kind of energy is left for you to step up your struggle. If you accept your enemies as they are and then you do nothing?” So these two questions, I think they are linked to each other. And I think that the elements of the answers to these questions have already been offered in the Dharma talks. But we need to work with ourselves, we have to practice mindful breathing, mindful walking, looking deeply, and recognize all the seeds in order to see the true nature of interbeing, then we could understand the real answers to these questions—not only as theory, but also as practice.

“Why don’t I love myself? Why is it so difficult for me to love myself?” The question can be answered by yourself, if you look into what you call “love,” what you call “self.” You have an idea of love, an idea of self, that is very vague. If you look deeply into what you call love, if you look deeply into what you call self, then you will not feel that way anymore. Self is made of what? Of non-self elements. Looking into yourself deeply, you can see all the non-self elements within you.

When I look into my store consciousness, I see the seed of hate, the seed of fear, the seed of jealousy, but I also can see the seed of generosity, the seed of compassion, the seed of understanding. So these seeds must be opposing each other, fighting each other within me, like good and evil fighting, the angel and the beast. They are always fighting within me. How could I have peace at all? It seems that you have something in you that you are not ready to accept. There is a judge in you, that is a seed, and there is a criminal that is being judged in you, and both are not working together in you. So there is a deep division in you, a deep sense of duality within yourself, and that is why you feel that you are alienated from yourself. You cannot love yourself, you cannot accept yourself. But if you know how to look at things in the light of interbeing, you know that everything is linked to everything else and the garbage can always serve as the food for the growth of the flower.

The other day I said that while walking in the Upper Hamlet, enjoying so much the flowers, the vegetation, the beauty, I came to a place where I saw there was some excrement left by a dog or something like that. I told the children I did not mind because I have a great trust in the earth. Earth is great, earth has a big power of transformation, and I know that earth will be able to transform the dirty things into nutritive elements soon for the vegetation. So I still continued to smile, and I didn’t mind at all. I saw the interbeing nature of the two things, the flower and the excrement. Looking in one, I saw the other.

The same thing is true with garbage and flower, afflictions and compassion and happiness. All mental formations in us are of an organic nature. If we know how to take care, to embrace, we will be able to transform and we will make the afflictions into the kind of nutriment that will grow, that will help my wisdom, my understanding, my love, my compassion, to grow. If you have that kind of insight into yourself, that both garbage and flowers inter-are, you would be able to accept the negative things in you in the way an organic gardener would be able to accept the garbage in her garden, because she knows that she needs the garbage in order to nourish her flowers. You are no longer caught in the dualistic view, you suffer much less.

Then when you look back, look deeply into your so-called self, you see that your self is made of non-self elements. What you don’t like in you, you are not responsible for alone. Your society, your parents, your ancestors are equally responsible. They have transmitted those seeds to you because they have not had a chance to recognize them. They did not have a chance to learn how to transform them, that is why they have transmitted them to you. Now you have an opportunity to recognize them, to learn ways to transform them, and you take the vow to transform them for your sake and for the sake of your ancestors, your parents, your society. That is the vow of a great being, of a bodhisattva.

So if you understand things like that, you will not say, “Why don’t I love myself?” It is possible to love yourself. The way offered in Plum Village is very concrete, how to love yourself. Your self, first of all, is made of your body. You love yourself by the way you eat, you drink, you rest, you relax. You don’t love yourself because you don’t practice these things, you don’t allow your body to rest. You force your body to consume the things that destroy it. So how to love your body, it is written down very clearly in the teaching of Plum Village: mindfully eating, mindfully consuming, mindfully allowing your body to rest and to restore itself. When we come to Plum Village, we have to learn these things. Sometimes you don’t love yourself, you destroy yourself, and yet you don’t know. The Buddha said that there are people who think that they are the lovers of themselves, but in fact they are enemies of themselves. They are doing harmful things to themselves, they are destroying themselves, and yet they think that they are loving themselves. They destroy themselves with their lack of mindfulness in eating, in drinking, in dealing with their body, with their feelings, with their consciousness.

When you have a feeling—pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral—do you know how to recognize it? Do you know how to embrace it? To calm it? That is the process of loving. When you come to Plum Village, you have to learn these methods of recognizing, accepting, calming, and transforming. To love means to practice—to practice looking, seeing, understanding, and transforming. When you love yourself like that, you love other people also. You love your ancestors, you love your parents, you love your children and their children, and you love us all by taking good care of yourself and loving yourself. Because you are made of us. Your self is made of non-self elements, including ancestors, clouds, sky, river, forest, and us.

You may say, “I want to love myself, but I don’t feel that I can love myself.” If you understand the teaching, if you can look into yourself and the nature of love, you see that love is a process of practice. Unless you practice, according to the teaching, you are not loving yourself at all, and not loving yourself, you cannot love anyone. Because self-love is at the same time the love for others. The moment when you know how to breathe in mindfully and smile, you make yourself feel better and you make the person in front of you, behind you, feel better also.

As far as hate is concerned, it is the same. You say that there is a lot of social injustice and other people are doing evil things to destroy themselves, to destroy you, to destroy the world, and it feels good to be angry at them. But who are they, who are you? You feel that you have to do something to help the world, to help society, but who is the world, who is the society?

When you see delinquent children, caught in drugs, in violence, and locked up in prisons, do you think that you should hate them or you should love them? You should take care of them. Why do they behave like that? Why do they look for drugs? Why do they have recourse to violence? Why do they oppose their parents, their society? There must be reasons why they do so. One day they may kill you, they may use a gun and shoot you down, they may burn your car. Of course, you can get angry at them, you can fight them, and if you have a gun you might like to shoot them down before they shoot you. But that doesn’t prevent them from being the victims of society, of their education, of their ancestors, because they have not been well taken care of. Punishing them would not help them; there must be another way to help them. Killing them would not help them.

There was a sea pirate who raped a small girl of twelve years old on a refugee boat. Her father tried to intervene, and they threw her father into the ocean and he drowned. After the girl was raped, she was so ashamed, she suffered so much—also because of the death of her father—she jumped into the ocean and drowned.

That kind of tragedy took place almost every day when there were boat people. There was not a day when we did not receive news like that in the office of the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation in Paris during the war. I remember the morning when I read the report about that girl, I did not eat my breakfast, I went into the woods. I practiced walking meditation, embracing the trees, and so on. Because I felt I was being raped and I was one with that child. I was angry at first. But I knew that I had to take good care of myself, because if I let the anger overwhelm me, make me paralyzed, then I could not go on with the work I should do, the work of peace and taking care of the victims of the war. Because at that time, at the office of the Buddhist Peace Delegation in Paris, we took care of providing the delegations in the peace talks with real information, trying to stop the war, and trying to relieve the suffering of war victims, including orphans and so on. At that time we were able to get support for more than 8,000 war orphans to continue to live and to go to school. So we could not afford to be paralyzed by such news that came every day into the office, so we had to practice together. Without mindful breathing, mindful walking, and renewing ourselves, how could we go on with our work when we were flooded with information like that about the war?

That night in sitting meditation, I saw myself born in a fishing village along the coast of Thailand, because I was meditating on the sea pirate. I saw myself as born in the family of a poor fisherman, and my father was very poor. My mother also was very poor. Poverty had been there for many generations. My father got drunk every night because the work was so hard and he earned so little, and he beat me every time he got drunk. My mother did not know to read and to write, did not know how to raise a child, and I became a delinquent child, playing with other delinquent children in the village along the coast of Thailand. At the age of 12, I already followed my father to the sea to help him with the fishing. I had seen girls and boys who were dressed in beautiful dress, who went to school in their beautiful automobiles, and I felt that I would never enjoy that kind of life at all.

Now I am a fisherman on my own. I have my fishing boat, and yesterday someone told me that the refugees very often bring with them some gold, and if I just go and take that gold just one time, I will be able to get out of this kind of chronic poverty and that will give me a chance to live like other people. So without understanding, without compassion, just with that kind of aspiration, I agreed to go with him as a sea pirate. When out in the sea I saw the other pirates robbing and raping the girl, I felt these negative seeds in me also come up very strong—there is no policeman around, there is freedom, you can do everything you like here, nobody sees you—so I became a sea pirate, and I raped the twelve-year-old girl, and she jumped into the river. Nobody knows. I have some gold now.

If you are there on the boat and if you have a gun, you can shoot me, I will die. Yes, I will die and that is the end of my life. You shoot me, yes; you can prevent me from raping the girl, yes; but you cannot help me. No one has helped me since the time I was born until I became a 18-year-old fisherman. No one has tried to help me—no educator, no politician, no one has done anything to help me. My family has been locked in the situation of chronic poverty for many hundreds of years. I died, but you did not help me.

In my meditation, I saw the sea pirate. And I saw also that that night along the coast of Thailand, 200-300 babies were born to poor fishermen. I saw very clearly that if no one tried to help them, then in 18 years many of them would become sea pirates. If you were born into the situation of that sea pirate, if I were born into the situation of that pirate, then you and I could become sea pirates in 18 years. So when I was able to see that, compassion began to spring up in my heart, and suddenly I accepted the sea pirate.

You have to do something to help them, otherwise they will become sea pirates. Shooting them is okay, but it does not solve the problem. Locking up the people who use drugs and who do violence is okay, but that is not the best thing to do. There are better things to do. There are things you can do to prevent them from being what they are now, and that is the work of love. In the enemy, you can see the beloved one. That does not mean that I would allow them to continue the crime, the violence, to destroy. I would do whatever I could to prevent them from causing harm, but that does not prevent me from loving them. Compassion is another kind of energy.

You say that anger is a formidable source of energy that pushes you to act. But anger prevents you from being clear in mind, from being clear sighted. Anger cannot give you lucidity, and in anger you can do many wrong things. As parents, we should not teach our children when we are angry. Teaching our children when we are angry is not the best time. It does not mean that we should not teach them, but we teach them only when we are no longer angry. We don’t teach with the energy of anger, we teach only with the energy of love, of compassion. That is true with the sea pirates, with the people who are destroying life. We have to act, but we should not use the energy of anger as fuel. We have to use the energy of sacrifice, the energy of compassion.

Great beings like the Buddha or Jesus Christ, they know the power of compassion, of love. And there are people among us who are ready to suffer, to die, for love. Please don’t underestimate the power of compassion, of love. With the energy of compassion in you, you continue to remain lucid and understanding is there. When understanding is there, you will not make a mistake. You are motivated by love, but love is born from understanding.

[Bell]

Many of us are motivated by the desire to do something for social change, for restoring social justice. But many of us get frustrated after a period of time because we don’t know how to take care of ourselves. We think that the evil is only in the other side, but we know that the evil is within us. Craving, anger, delusion, jealousy—they are in us. If we don’t know how to take care of them, to reduce their importance, to help the positive qualities in us grow, we would not be able to continue our work, and we’ll be discouraged very soon, overwhelmed by despair. There are many groups of young people who are strongly motivated by the desire for social action, but because they don’t know how to take good care of themselves, they don’t know how to live and work with harmony among themselves, they give up the struggle after some time.

That is why it is very important that we take good care of ourselves, and then learn to look at the other people not only as criminals but also as victims. Of course, we should do everything we can to stop them in the course of their destruction. But we should also see that they are to be helped at the same time. We should be able to make it very clear to them that, “If you do this, we will try to stop you by whatever means we feel that we need, but we will do it with love and compassion. We will try to stop you, to prevent you from doing whatever you try to do to us and to your victims, but that does not mean that we are acting with hatred or anger. No, we do that with love. If you know how to go in that direction, we will support you wholeheartedly because it is our desire, our hope, that you move in the direction of harmony, of nondiscrimination, of social equality.”

We have to make it very clear, because in that person there is a friend, and there is an enemy in him or in her at the same time. The enemy is the negative seeds, and the friend is the positive seeds. We should not kill the friend in him, we should only kill the enemy in him; and to kill the enemy in him is to recognize the negative seed in him and try to transform it, to not allow the situation to be favorable for the continuation of crime and destruction.

So that is a strategy, because to practice you need a strategy. You need a lot of intelligence, of deep looking, and you also need a lot of compassion and love. In the context of social change, we have to practice together. We have to unite our insights. We have to bring our compassion and insight together in order to succeed. We know that only love, only compassion and understanding, can really bring a change, because hatred cannot be removed by hatred. This is something said by the Buddha in the Dhammapada, hatred can never be removed by hatred.

[Bell]

Dear Friends,

These dharma talk transcriptions are of teachings given by the Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh in Plum Village or in various retreats around the world. The teachings traverse all areas of concern to practitioners, from dealing with difficult emotions, to realizing the interbeing nature of ourselves and all things, and many more.

This project operates from ‘Dana’, generosity, so these talks are available for everyone. You may forward and redistribute them via email, and you may also print them and distribute them to members of your Sangha. The purpose of this is to make Thay’s teachings available to as many people who would like to receive them as possible. The only thing we ask is that you please circulate them as they are, please do not distribute or reproduce them in altered form or edit them in any way.

If you would like to support the transcribing of these Dharma talks or you would like to contribute to the works of the Unified Buddhist Church, please click Giving to Unified Buddhist Church.

For information about the Transcription Project and for archives of Dharma Talks, please visit our web site http://www.plumvillage.org/

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.